Sitting in Truth

The process of Sitting in Truth requires deep reflection and a willingness to make ourselves uncomfortable. By reflecting on what we believe to be true, we allow ourselves to critically examine our own beliefs, our truths, and where they have come from. By creating space within ourselves, we make space for others to feel seen, heard, and understood. This is where healing can truly begin.

Check in on yourself throughout this journey, which statements spark feelings of shame? Disbelief? Anger? Take note of when, how, and why these feelings emerge.

The uncomfortable truth is that Canada’s mistreatment of Indigenous peoples is nothing new; it stems from a deliberate effort spanning hundreds of years, seeking to exploit traditional land and eliminate cultures (1). Canada is at a critical juncture in its relationship with Indigenous peoples as we begin to acknowledge our colonial roots and discuss reconciliation and how it may be achieved (2). Although we cannot change history, we must recognize the unethical treatment of Indigenous people as we focus on Sitting in Truth.

Before reading this section, consider what you think you know about Canada’s history. Then, in your journal, write down what facts you believe to be true regarding the Indian Act, Sixties Scoop, Indian Residential Schools, and the systems that continually oppress Indigenous people.

A Brief Look Into Canadian History

First Nations people inhabited Turtle Island (North America) for thousands of years before Europeans arrived on the continent (2). The timeline of Indigenous and non-Indigenous people in Canada started in the 1400s. Below we aim to provide a very brief historical context.

For that reason, we encourage you to dive deeper into the Timeline of Indigenous People from Canadian Encyclopedia (18).

Indigenous and settler relationships started collaboratively to build alliances, ensure safety, and share culture. Indigenous technology and knowledge of hunting, trapping, and fishing were vital to European survival. In exchange, Indigenous people had access to European weaponry and goods. A relationship of mutual opportunity and a sharing of cultures enabled Europeans to settle in this unknown territory.

As Indigenous communities became devastated by smallpox, measles, and tuberculosis, settlers saw an advantage to deliberately spread illness (19). Diminishing Indigenous populations and the growth of French colonists led to the allyship between English and Indigenous peoples. This allyship launched the 150-year war between English communities and Indigenous Nations residing in the Ontario/Quebec region against the French settlers (19).

Understanding the importance of having Indigenous alliances, the English signed treaties that reinforced trust, peace, and mutual interest. Royal Proclamations and Treaties were signed to establish how the government could acquire land by protecting the rights of Indigenous peoples and negotiating on a nation-to-nation basis (19). These Royal Proclamations and Treaties legally protected Indigenous peoples and created a large trust fund for purchased land.

During this time, Indigenous people continued to experience disease, destruction of their culture, and annihilation of their primary food sources, such as buffalo; these experiences resulted from continuous betrayal by the people assumed to be their allies (18). Settlers realized that these Royal Proclamations and Treaties protected Indigenous people and came with rights to land and a large trust fund (18). The goal was to eliminate treaty rights so that the government could access the land and trust fund. Settlers concluded that if they eliminated Indigenous populations, money and resources would default to the Canadian Government. In response, the Canadian government introduced the Indian Act with the purpose of stripping Indigenous people of their identities.

The Indian Act and a series of reports by the government proposed that the best way to assimilate Indigenous people into Euro-Canadian culture was to separate children from their parents. If parents could not pass on their knowledge and culture, their children would no longer identify as Indigenous. As a result, Indigenous culture would eventually be lost, resulting in the Canadian Government gaining access to the protected land and Indigenous trust fund. The Canadian Government then introduced Residential Schools to assimilate Indigenous children.

Around the 1950s, several studies revealed that Residential Schools were ineffective at eliminating the ‘Indian Problem,’ and the government began to consider new ways to separate Indigenous children from their families (19), as a result, Residential Schools evolved into Day Schools (19). Then the Canadian Government started a marketing campaign to have Indigenous children adopted into non-Indigenous homes, which we now refer to as the 60s Scoop. At this time the government began to pay marketing teams to promote the adoption and fostering of Indigenous children into non-Indigenous families across the globe.

Now that you have a brief understanding of Canada’s history with Indigenous people, we will expand on some of the concepts covered above. Continue reading to further your understanding of the Indian Act, Residential Schools, and the 60s Scoop in further detail.

The Indian Act

First introduced in 1886, the Canadian Government created the Indian Act as a strategy to eradicate Indigenous cultures (3). It is a common misconception that the Indian Act was created to help Indigenous peoples when, in fact, the opposite is true. At the time of its creation, the Indian Act failed to recognize key identities within Indigenous cultures, specifically, Métis and Inuit people; this was a strategy by the Canadian government to create division among the people (3).

Bob Joseph discusses his book “21 Things You May Not Know About the Indian Act” in The Indian Act Explained video (5). We encourage you to take the time to watch the video as it addresses many misconceptions about the Indian Act and may help you to develop a deeper understanding.

Activity

Learn More

Listen to The Indian Act podcast (6) to gain further insight.

Questions for Critical Reflection

How is the Indian Act continually oppressing Indigenous people?

Who does the Indian Act Benefit?

Why do you think some Indigenous people do not want to eliminate the Indian Act while others do?

Canada’s Dark History: A Look at Residential Schools

The Indian Residential School System in Canada was yet another strategy by the Canadian Government, in partnership with the Roman Catholic and Anglican Church, to abolish Indigenous culture. Residential Schools began in the late 1800s with 139 active institutions at the height of enrolment, with approximately 150,000 children attending (1).

For a more specific timeline, watch Residential Schools in Canada: A Timeline (7).

Children were torn away from their families and placed into Euro-Canadian schools, where it was forbidden to practice their traditions or speak their languages (2) [Image - (20)]. In addition, children attending Residential Schools often faced severe emotional, physical, spiritual, and sexual abuse. By cutting the connection between the children in these schools and their cultural values, the Canadian Government created a system that “prevented the transmission of cultural values and identities from one generation to the next” (2), determining to erase Indigenous identities.

For the next part of this journey, we ask that you listen to Historica Canada’s 3 Part Podcast Series (17) on First Nations, Métis and Inuit experiences, acknowledging Canada’s dark history.

Photo: Kent Monkman | The Scream | 2017 | Acrylic on canvas | 84” x 126” | Collection of the Denver Art Museum | Image courtesy of the artist

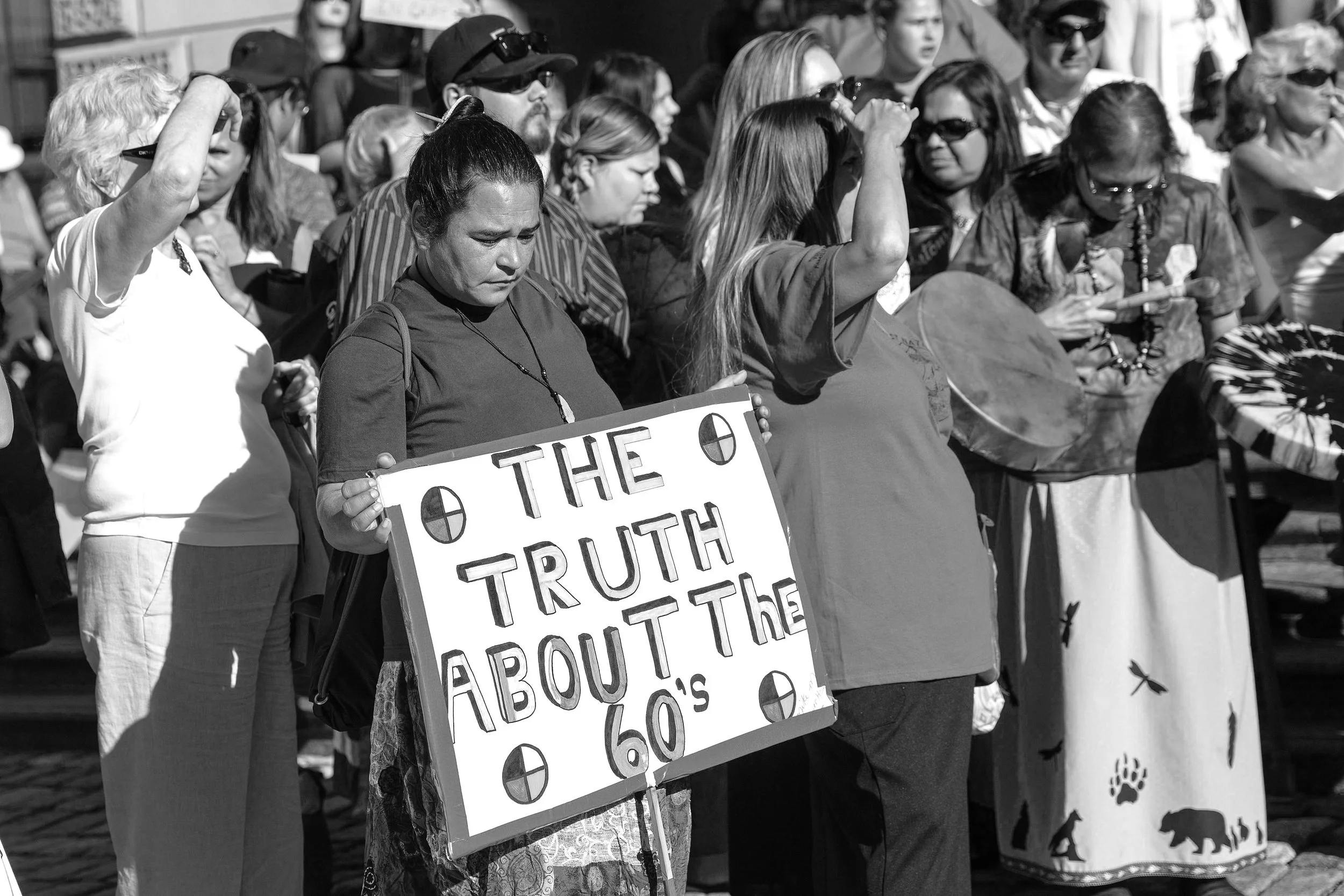

The Sixties Scoop

Watch the Sixties Scoop (8) video, to learn more about this catch-all name for a series of policies enacted by provincial child welfare authorities starting in the 1950s. The Sixties Scoop refers to the mass removal of Indigenous children from their families without parental or band consent and placing them into welfare systems (9). Thousands of Indigenous children were placed into state care and eventually adopted into white families across Canada and the United States (10). These children lost their names, languages, cultures, connections to their families, and ultimately their sense of belonging. An alarming number of Indigenous children were apprehended in the 1960s and onward, with roughly one-third of all children in welfare systems being of Indigenous descent in 1970. The effects of the Sixties Scoop have rippling effects that persist today as many Indigenous people remain displaced, and potentially unaware of their heritage. Many people believe that these practices still exist within the child welfare system. In recent years, calls to investigate the current adoption and foster systems have been more frequent.

Canada has sought to change its child welfare policies to better protect and care for Indigenous children. However, these policies must be continually reviewed and revised to ensure that the complexities of Indigenous child welfare are not underestimated (9).

Activity

Now that you know more about the Sixties Scoop, we invite you to engage in Della's Story, a virtual escape room (11). The interactive room requires 3 to 8 players to participate and aims to place you in the shoes of a 60’s scoop survivor.

Critical Reflection for Della's Story

Is there any information about the Sixties Scoop that you did not previously know?

How can we engage non-Indigenous people in innovative ways to learn more about Canadian History?

Learn More

Consider watching this short film, “Sisters & Brothers” (12), which draws parallels between the destruction of buffalo and Residential Schools in a way that provokes emotions and raises awareness.

Closing Statement

Now that you have completed the first section of our toolkit, Sitting in Truth, we would like you to reflect on some of the things you have learned so far. Refer to the list you wrote about what you knew before beginning this section. Were you already aware of Canada’s dark history? Or were some of these facts surprising to you? Now that you have done further research, was the information you knew accurate? Was it what you expected?

Now, ask yourself, why is the general public only just beginning to understand the horrors that Indigenous people faced? We ask that you take the time to reflect on this portion of the toolkit in your journal. Answer the questions listed above and any that you’d like to touch on from the individual sections.

Food for thought (another journaling opportunity): Who writes our history books? Who is determining the facts? Consider the perspective lens you are peering through when you look back in time. How does this shift the narrative?

It is important to note that this is a very brief explanation of Canadian history. It is not all-encompassing. Sitting in Truth acknowledges centuries worth of history, and due to this, several details have been left out. Take a look through our “supplementary resources” section for opportunities to further your understanding before moving onto the next sections of the toolkit.

Supplementary Learning

Google these terms and explore related resources:

Segregated hospitals

Creation of the RCMP

Creation of the Canada food guide

Forced sterilization

The development of the electric chair

Starlight Tours

Watch “Doing the work: What settlers need to know”. In this virtual Q&A, a mixed panel of knowledge keepers, elders, and settlers discuss what settlers need to know about the residential schools system, and its continuous harmful impacts on Indigenous communities (22).

Read “Indian Hospitals in Canada” (23). This article details the segregation that Indigenous Peoples faced in medical care.

Read “The dark history of Canada's Food Guide: How experiments on Indigenous children shaped nutrition policy” (24). This article explains the dark history behind the creation of the Canadian food guide.

Key Terms

-

“A practice of domination, which involves the subjugation of one people to another; One society gradually expanding by incorporating adjacent territory and settling its people on the newly conquered territory” (13).

-

“The destruction of the political and social institutions of the targeted group. The land is seized, populations are forcibly transferred, and their movement is restricted. Languages are banned. Spiritual leaders are persecuted, spiritual practices are forbidden, and objects of spiritual value are confiscated and destroyed. Families are disrupted to prevent the transmission of cultural values and identity from one generation to the next” (14).

-

“An intentional, culturally sensitive and appropriate approach to adding Indigenous ideas, concepts, and practices into curricula, when and where it is appropriate; A strategic set of changes to policies, procedures, and practices that increase inclusion, break down barriers and realign institutional, college and school outcomes without harm to previously established goals; An iterative developmental approach to understanding Canada’s colonial history and the more contemporary issues impacting Indigenous people. Engaging in critical reflections from a professional and/or personal perspective about how to build safe and ethical spaces for Indigenous knowledge, worldviews, and practices” (15).

-

“The rights, advantages, and protections enjoyed by some at the expense of and beyond the rights, advantages, and protections available to others” (16).

-

“A systemic relationship of unequal power between white people and peoples of colour” (16).

-

“Vicarious trauma is a process of change resulting from empathetic engagement with trauma survivors. Anyone who engages empathetically with survivors of traumatic incidents, torture, and material relating to their trauma, is potentially affected” (21).

Knowledge Sharing Series

Truth can hurt. Sometimes, it can be challenging, uncomfortable, and difficult to hear. But when our truths are shared, it has the power to heal.

Sisters Judy and Jody Bear will led us through “Sitting in Truth,” sharing the story of their lives. Jody and Judy’s story is one of hardship, but also of resilience. Together, they reflected on the impact of residential schools and the powerful journey to overcome intergenerational trauma. The lesson here is Ahkameyimok: don’t give up, keep trying and continue persevering.